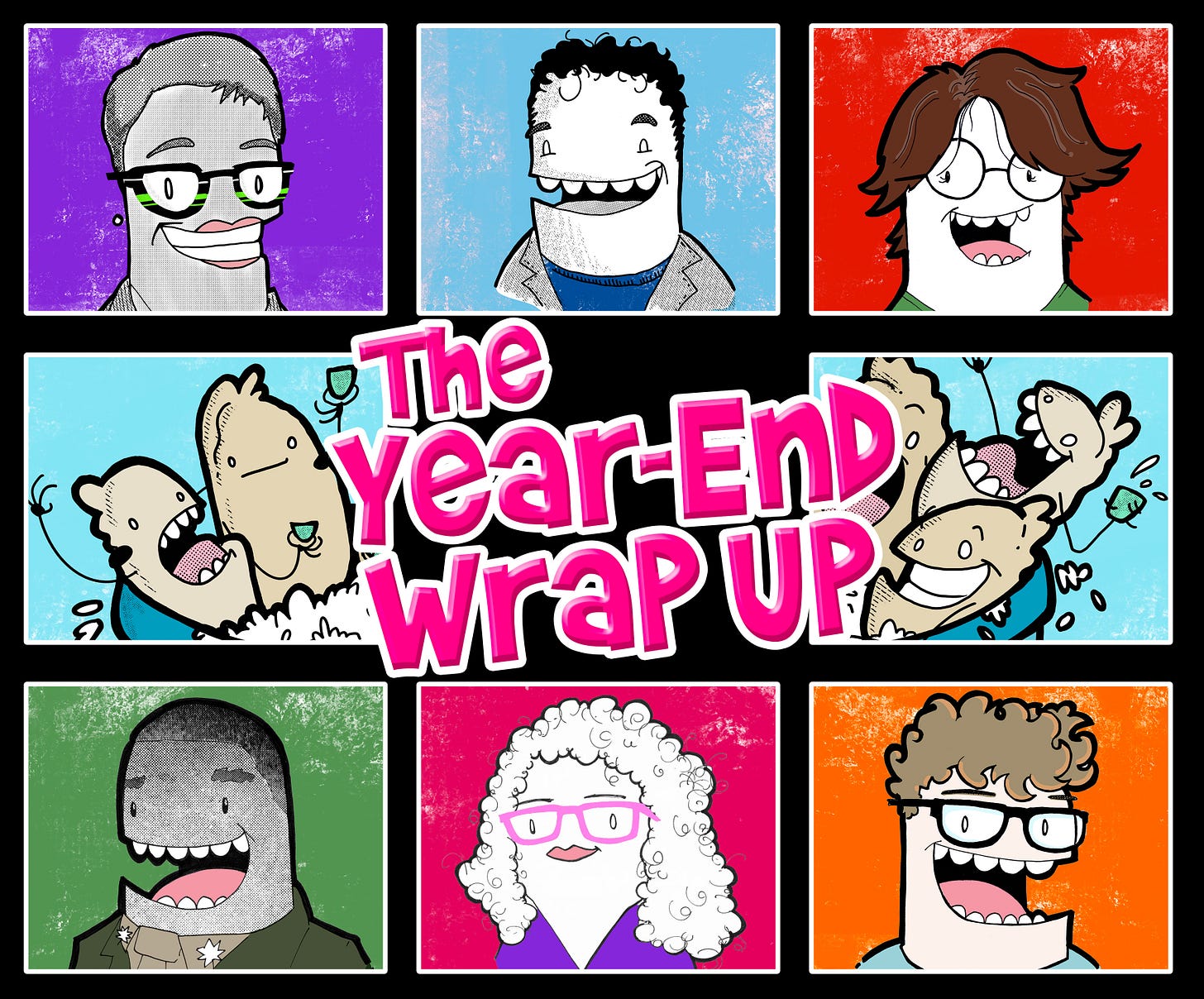

Thanks again to Jamahl Evans, Tiziana Casciaro, Judith Athaide, Andrew Escobar, Lisa Oldridge, and the Dumpling Gang for their willingness to take this journey with me.

TRANSCRIPT

Matt (Voice-over)

Welcome back to Sound-Up Governance. Heading into the end of 2022. I realized that I have so much cool and unused material from the first four months of the podcast. And it wasn't unused because it wasn't awesome. To give you a sense of how I make the Sound-Up Governance sausage, each interview is at least 45 minutes, which already gives me way more material than I need for an episode. Before I start the interview, I already have an idea of what I want the narrative flow of the episode to look like. Invariably, the conversations go on brilliant tangents that just don't fit the narrative. So this episode is like a collection of treasures that I've gathered along the way from all the brilliant people I've spoken with. Let's start with Lieutenant Colonel Jamahl Evans of the US Marine Corps. Listening to Jamahl, I wondered how a super disciplined and hierarchical organization like the Marines would deal with ultra high potential superstars. Here's what he told me.

Jamahl Evans

I can't speak for every Marine throughout history or throughout the organization. But I will say my approach to it is everybody has responsibility and everybody deserves an opportunity. And if you if you wind up focusing on one individual, because they are outstanding in what they do, there are two negative possibilities with that. First is overburdening that individual. The second is ostracizing that person's peers. So when you do that, you're saying, "well, this, this is my my number one person, this is my superstar." And you're not giving opportunities or responsibilities to your other people. That's how you can quickly build resentment in an organization. Because you have one person that's doing all the work. And it gets even worse if they're not recognized and acknowledged. They're doing all the work, and you have other people who want the opportunities, but for some reason, they're not trusted with them. So this is one thing that I love about being in the Marines. If I look at your collar, and I know where you work, I know that you're supposed to be able to do a function. So you can be great, you can be mediocre, you can be subpar. But if I look at your ability, where you're assigned, and I know that that's your function, you're getting the task! And it's on senior leaders to eliminate the fear of what could happen if you don't give it to your best person. I worked with a with a he was a Master Sergeant at the time. We had a young Marine, junior enlisted Marine, was a Lance Corporal who was extremely smart in the budget and accounting system. And he wanted to deploy somewhere. He had never deployed since he had been in the office. And that was in an area where we did a lot of deployments. So the chief, the Master Sergeant came in and he said, you know, "we need to deploy him." I said, "got it! How are we on on backup when he leaves? Because he's doing a lot of stuff!" And the chief looked at me and he said, "Sir, we are not one deep, and if we are one deep, we're gonna find out!" So I said, I said, "Absolutely agree. Absolutely agree." And we got him out on a deployment. And guess what? The unit work just fine. And we had two Marines who had not really had their had their moment in the limelight, so to speak, kind of flying under the radar who were required to step up, he stepped up in in great manner. So that is how you you get around the "this is my superstar. This is my rock star." And it happens in every organization. But it's again, once again on that senior leader to see that and say, "okay, yes, this person is highly dependable. Yes, this person is highly capable. But these other people need an opportunity. And I want to see how many of them can perform close to this other one."

Matt (Voice-over)

Speaking of multiple people vying for opportunity and influence, I asked Professor Tatiana Casciaro about one of my favorite idiosyncrasies of boards of directors: the fact that every director comes into the room with just one vote and no real authority on their own, making them equals in a way. I did this interview months and months before the launch of Ground-Up Governance, back when I thought I might just write a book instead. Tiziana is so brilliant! I really love her response here,

Tiziana Casciaro

I would say that it is not the case that every director has equal power. I will say that every director has equal authority, but not equal power. Because they all formally get to participate in the decision of the board in equal ways. So they all have an equal amount of pressure they can put on the decision making of the board. But their actual power, which is broader than authority, comes from whether they control resources that other board members value. And therefore they give me as one of those board members extra leeway, extra influence. So suppose I want the board to decide to make a certain move. And not everybody on the board kind of likes that idea. And if they don't like it, it's going to be very hard for me to get there and make that move. What I can do is gain an understanding of what the other board members want, need, desire. And if I get to access those resources, and again, that could be material resources, it could be that I know that you really, really, really want to connect with a certain company, for whatever purpose you have in your brain. And I happen to have a way to help you do that. That's something you want that has nothing to do with your roles on the board. And this is where you see how easily the interests of the board members can become complicated, and almost disconnected from the ultimate purpose of the board in a formal understanding of that purpose. So but if I understand all the things you want, as my fellow board member, I can dangle those resources in front of you to persuade you that actually coming on board with the move I want the board to make, is actually a good idea. Because in exchange for that, I will give you something that you have at heart. And it's also an ethically potentially treacherous territory very quickly, because the interests that the people bring to the board as directors are varied, and sometimes they're conflicting, and sometimes are profoundly disconnected from the mission of the board. But they are there, they are in the action. And they are part of who has power and who does not in the board, even though formally they all look the same.

Matt (Voice-over)

You remember Judith Athaide, who went from teaching in Brandon, Manitoba to being one of Canada's most in demand Corporate Directors? Well, I asked her a bit about that journey, because as you'll hear me say in a second, she was making it sound a bit too easy.

Matt

So you made it sound easy. This like starting where you started and then ending up as this like, superstar director, but I suspect it wasn't so much of a straight line. How did that even happen? So you, you started in this situation where you're, you're eager to learn you're you understood you didn't know what you're doing, you went out and learned some stuff. But how did that really get you from there to being where you are now? Because you're, you're kind of a hot commodity!

Judith Athaide

Matt, I wouldn't say I'm a hot commodity. Let's start with that. I would not use the words a hot commodity. I am a believer that not every director is right for every organization all the time. I'm very thoughtful about it. So So I would say that when I finished the DEP program, it took a lot of networking. It took a lot of conversations of laying the seeds with with my colleagues and the community to say, "I'm interested here are the skill sets that I have, here are the skill sets I don't have. So here's where I can contribute." And it wasn't overnight. I mean, when you think about my first for profit, large organization Accenture was 2003. We're now 19 years later, my first board was 1989. We're now 33, 34 years later. So it hasn't been high velocity. It has been about you know, investing, learning, growing and spending my time paying my you know, paying my dues and contributing throughout private, public, crown, not for profit. And I continue to do that. The other thing is I would say I like to be thoughtful about the organizations that I contribute to. Part of it is a portfolio approach so that I can bring value to different organizations, different sectors, and take value from them to the next sector. Part of it is, obviously, having the time and having the schedule that allows it. And part of it is getting really comfortable with the chairs of the boards and the chairs of the committee. I think that's really important that I can work with them. And as one of my mentors said to me 20 years ago, he said, "you think it is hard to get onto a board? Let me assure you, it is much, much more difficult to get off a board. So be very careful when you say 'yes,' because it's very hard to say, 'I need to exit.'" And so I've always kept that in mind when I look at an opportunity. I have to be able to commit to working through the good times and the less good times with the board as a whole. So that that having a relationship with my fellow board members, having trust in them, they in me and developing a relationship where we don't agree all the time. But we have the common objective of doing what's the right thing for the organization and stakeholders is really important.

Matt (Voice-over)

Okay, so that was clearly not as easy as it originally sounded. Judith is now realizing the results of over 30 years of investment of time, talent, training and well, general awesomeness. During my interview with Andrew Escobar, for episode five, I couldn't pass up the opportunity to ask a young corporate director about his perspectives on ESG, a commonly used initialism that stands for Environment, Social and Governance. Here's what he had to say.

Andrew Escobar

All of all of those three are still very important right in, in my board work. The environment, society, or social responsibility, governance. But I tend to focus on the governance piece. Because that's, you know, what my role is, as a board member. I'm deeply engaged in the governance of one organization, and hopefully many others throughout my career. While all three of those are important, and critical, I think governance is that first piece to solve, though. I don't think that you can tackle the E and the S without first tackling the G. The problems that we're trying to solve, the opportunities that are in front of us within our environmental responsibility, our social responsibility, are huge. Right? How do you though, as an organization, even begin to grapple with them if you haven't self governance? So that, to me, is my focus. I recognize that, first and foremost, like we have a climate catastrophe on our hands. What are we doing to solve for that? Society is not right, right? There's, there's, there's so much more we can do. But I know that we need to have broad solutions for these things. And that without governance, we cannot begin to solve for them. So that is where I focus.

Matt (Voice-over)

Incidentally, Andrew and I are pretty well aligned here. When I use the term ESG, I typically think of it as "the G of E and S," or the governance of environmental and social factors. I shared that definition with Lisa Oldridge, who's an ESG guru, back when we spoke for episode three.

Lisa

Yeah, that is a good question. So I mean, I'm not sure if I would use ESG if I were to come up with it. And this is not me, just being sneaky, but I would probably say non-financial performance measurement. Right? Because so I like "the G of E and S." That, that makes sense. But really, E, S and G are just like, arbitrary buckets of is it about, you know, is it about the natural world? Is it about the people? Or is it about the quality of the ethics and the decision making and all that together? And you should be performing well in all those things. And it's not, you know, return on capital employed as a measurement, for example, right? But there's a whole bunch of really cool things in there that are a lot of it is maybe the squishy stuff and if you take S for example, I'm sure you could do the double click and find things like, you know, engagement and all these things that used to be squishy, but now we've got the ability to go to do the research in the data audit, and it's like now you can find really cool stuff like George Serafeim did that work with his group where it's like, with engagement, not only if you not only do you find a statistically significant performance improvement when you have high engagement defined as I think it's sort of like the degree to which the person is aligned with this is this is World at Work, I think they did like some ungodly amount of crunching of the of the data. So not only if the person is sort of aligned with the purpose of the organization and feels like they have, they're engaged with it, they did data cuts on it, and it was like, there was a bigger statistical outperformance, the more down in the, to use a hierarchy, the more it was sort of, the more that marinated in the company sort of down to the more junior levels and the front line. And you know, you and I go "duh, of course!" Right? Like culture is actually a strategic asset. And that's maybe where I start to pull the whole sort of ESG back towards, you know, material and decision useful and material to like the performance of the company. Now, I also come at it from a, maybe it's a bit of a Pollyanna place where I look at, sort of, there's, there's this... I'm going all over the place, but you're just gonna have to live with it. But Mark Carney's recent book, Values, he uses an infographic that he, I think, adapted from Impact Institute or something. And it's basically the spectrum of capital. And if you start all the way on the left hand side, which is the wrong side, it's like classic capitalism, you know, Milton Friedman, 1970, you know, "business of business is business," that's what some of this anti woke stuff, you know, Strive Capital and all this, you know, "we've lost the plot," it's whatever. That's that kind of a use of capital, whereby you're not really worried about externalities, it's okay, if the, the well site or the mine site or the, you know, it looks like Mordor or whatever, right? You're just gonna make a buck and get out. And then on the very other end of the spectrum is philanthropy. So from the optic of capital investment, you're losing it all on purpose, but you're losing it all. And then you can kind of move across that. So you know, you go, you go just to the right of Milton Friedman, and profit at all costs, then you start to get into things like "well, maybe we should worry about some of these so called ESG things in terms of risk or cost. So let's switch to LEDs, you know, let's not poison the water of the village we're trying to operate in." I'm being kind of crass, but you get the point. And then you can get into and it gets really interesting, because as you go over that if he as you sort of come over on that spectrum, I think that we're at a spot where you can, and I really believe this, we're at a spot now where there's a lot of businesses that can do things that enhance the natural world or social construct et cetera and make a market competitive return on a market competitive timeframe. Right? And, I mean, there's a bunch of things that are converging there, there's a demographic trend, and I think it's what 60% of workers under 35 want a business to be around for social reasons over profit. I don't think profit is unnecessary. I mean, that's the first it's the first ingredient in sustainability, because if you're not around the next year, it's a bit of a Pyrrhic victory, right? But there's also just these giant problems that need to have a lot of money thrown at them.

Matt (Voice-over)

To wrap up the year, let's go back to the Dumpling Gang. Oh, and I can't skip this chance to use the super cheesy Dumpling theme song. Hold on.

Music plays

Matt (Voice-over)

It's basically like I rewrote the Beverly Hills 90210 on our theme song or something. So dumb. Anyway, if you're not familiar with the Dumpling Gang, go back to the October 21st post on Ground-Up Governance and have a listen. I love this part of our conversation where we talked about how organizations fail when it comes to inclusion. I shared a bit of a ham-fisted example which my homie Mary Lee picked up and scored a touchdown or whatever sports metaphor you like.

Matt

If you brought a blind person into your group, this is something that we can all kind of imagine that we can visualize what it could be like to be blind. You wouldn't just say, "welcome to the group! You sort it out." Right? We would ask some questions and try to understand it and do our best even if we were clumsy at it to create conditions where they can participate. I and I try to and I don't I'm not saying I understand this. But I think it's important to assume every single person in any group needs that type of attention, not because they're blind but because they've got some thing that makes it difficult for them to feel engaged, included and optimized. Right? Is that fair?

Mary Lee

Yeah, I would say so because I don't, if you take that example and apply it to a marginalized, or

Dana Gray

Invisible disabilities

Mary Lee

Yeah, perfect, like any of those situations, or just any situation that's in the workplace, we don't take time to do any of that. Instead, we tell individuals that they need to fit in. Not directly. Inadvertently. Because then we give power to certain people, we give influence to, like you start seeing how decisions are made, and hence why you observe the you observe the environment, and then you decide the people sit in certain levels in the sandwich, and then things are done, as always, in a certain way. I think. At least in my experience, like, yeah, people don't stop and ask the questions or pause to ask somebody what their opinions are if they haven't spoken up at any of last three meetings. Any of those things are not taken into, I think, practice to, for, you know, for folks even to develop their own style of power or influence.

Dana Gray

Yeah, there's a sort of unspoken reinforcement of the status quo that people don't question.

Mary Lee

Yeah. And like expecting people to, I think it's like expecting folks to operate. And I always feel like the biggest group that I always go back to are those that, at least what I've observed, I don't, I wouldn't put myself in that bucket. But essentially, working professionals that have really great degrees that come to Canada, immigrate to Canada, and are trying to find their selves here. I find that group is often forced to figure out quickly in the first three years, "either fit in or get out" kind of feelings at workplaces. Because I've seen it and it's just like, and if we do say like "we make room for all different folks," like it's hard, it's hard. I just don't see it happening as often. Or done well, or just you know, provided

Matt

There's a really big "we want everyone to fit in as long as..."

Mary

Exactly, that's a great way to say it. It's like "you're doing a great job." But then it's all, "but you can improve on all these things." It's like what we're expecting. But so it is telling somebody, what they came into the office wearing is not good enough, the experiences that they carry is not good enough. Because "here's everything else we expect if you want to like rise to the top!" So yeah, so I do see that in what you describe about if it's conscious, I do believe it's conscious when you're a visible minority, at least I guess, in my experience. Yeah, it's conscious. Because even if you say it's unconscious, it's already built into my subconscious at this point, for working so long, like it's already built in you already. You know.

Matt (Voice-over)

And you know what, the thing that Mary is describing is precisely why I believe a change, a movement even, is overdue in corporate governance. Organizational decision making is not a function where we can afford to want people to fit in "as long as..." or where what someone wears isn't good enough, or where conformity to some absurd set of norms is what we should strive for. So, thanks to all the brilliant people who joined me on Sound-Up Governance this year. And thanks most of all to you. If you're listening, it means that you care enough about Ground-Up Governance or about me, or both, to be a paid subscriber. It really is a humbling and energizing experience to know that you're tuning in. I hope you've learned something over the past few months and I can't wait to keep the Ground-Up Governance ball rolling in 2023. Thanks again for listening.

Share this post